|

I want to tell you a fictional story about John and why he is sometimes robbed of the pleasure of moving to-dos to done. There is a little-known reason for this feeling of being overwhelmed and immobilized.

John understands the importance of having an external dedicated spot to park ideas and tasks. With admirable effort, he is now in the habit of parking those tasks, projects, and ideas into one trusted place. He started with a planner that his friend loved using. It was a vast improvement on his previous scraps of paper sprinkled around his home. After some time, though, he grew tired of erasing and re-writing as his priorities shifted throughout the week. He wanted a faster way to prioritize and reprioritize tasks at a moment’s notice. After an initial investigation, he decided that a digital app would improve his ability to keep up with his ever-changing schedule. He limited himself to two hours of research because of his proclivity to fall down the research rabbit hole. There were so many promising options, yet he was able to settle on Asana. Fast forward six months. John now transfers all his great ideas into the app, in addition to his personal and work tasks. He sorts them by importance and urgency and immediately feels a sense of control that was previously elusive. Excellent work, John! Let’s all give him a round of applause because this is a significant accomplishment. John marvels to his friend about this new habit. He is shocked that it has become second nature to plop nagging tasks into the app. They no longer nag him nor take him off task. Although he is quite pleased with his efforts, he wonders aloud why he occasionally feels slightly cagey when looking at his lists. He diligently prioritizes all tasks by importance and urgency, which is why the feeling is baffling. In talking to his friend, he discovers the root of his anxiety. Even with prioritization, there are so many competing tasks he could be doing at any given moment, and there are clearly not enough minutes in the day to tackle them all. So, what can John do to lessen this angst and increase his sense of accomplishment by the end of the day? An entire industry revolves around productivity and reaching goals, but today, I offer John two simple tactics to avoid feeling swamped. He already understands that the holy grail of productivity lies within the “important but not urgent” quadrant of the Eisenhower Matrix. Ironically, though, a different quadrant (“not important and not urgent”) is throwing him off balance. He forgot to apply a critical step of the organizing process to his task and project lists. He used this step successfully when clearing out his garage but did not realize he could apply it to his task list. Namely, he still needs to purge extraneous tasks and projects. Even though he prioritized his massive to-do list, it still feels daunting. After connecting physical and informational clutter, he downsizes his lists by eliminating non-important-non urgent tasks. A familiar feeling of liberation arises as he ruthlessly deletes one task after another. He recalls feeling the same way when victoriously pulling his car into his garage. After vanquishing the obvious dead weight, a smattering of projects give him pause. He is unsure whether these projects will bring him closer to his larger goals. He recalls details of the garage project for any relevant tactics. Sure enough, he remembers putting a few items in a box labeled with a future discard date. This purgatorial box had allowed him to determine whether he would miss the items after a few months. With this strategy in mind, he parks the final projects in a separate section of the app where they no longer visually bombard him. He wants to label this section appropriately so it still catches his eye but is not intrusive. He remembers reading about the “Someday/Maybes” list in David Allen’s Getting Things Done. John wants something a bit more memorable. He labels this section with the hyperbolic title, “I’m either a genius or delusional!” It injects a bit of humor into the process. He knows it will bring some levity to the app. John is now happily tackling his tasks one day at a time. Most evenings, he feels satisfied seeing his completed tasks leading him to essential goals. The whole process feels lighter. It is a massive accomplishment. He shares the good news with his friend, who treats him to a celebratory dinner. Like John, I use Asana to get ideas, tasks, and projects out of my head to focus on one task. It is easier than focusing on one task while simultaneously attempting to remember other tasks. I have no affiliation with this company but have tried various apps over the years, and I find Asana to be one of the better task apps on the market. Can you imagine employing John’s tactics on your task list? Perhaps this sounds fantastic, but your task lists aimlessly wander around the home on random bits of paper. There is hope. Contact me so we can map out your game plan and make this dreamy story your reality. Whether you use a task app or a paper planner, I can attest to the liberation from deleting irrelevant tasks and ideas from your lists. Have you ever felt relief in letting go of mistake purchases? Relive that moment by deleting ideas that once seemed brilliant but have lost their luster. When in doubt, use the Someday/Maybe list. You can relax, trusting your system to hold on to that idea until you have time to revisit it. Try these tactics to move away from a to-do list and towards a to-do-to-done list.

0 Comments

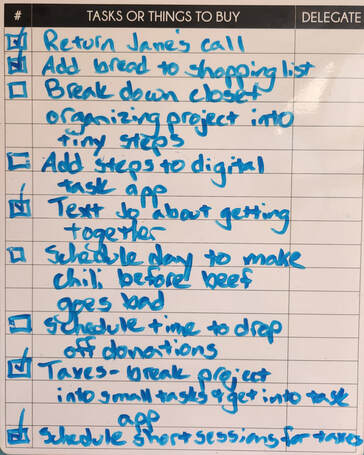

The Trap “I’ll remember,” you tell yourself. “I’ll remember,” clients tell me when I ask them how they will remember to tackle a task they want to accomplish before our next session. “I’ll remember,” I tell myself on the rare occasions when I forget to distrust this wily statement. It’s a trap. How many times have we all told ourselves that we would remember to do something, only to chastise ourselves a few days later when we forgot to do that thing we thought we would remember? These tasks might be small annoyances but collectively add up to a cluttered home of unfinished tasks and projects. I admire clients’ positivity, enthusiasm, and confidence when they make this statement. I also wonder if they will remember amidst all the unexpected situations that inevitably pop up between sessions, not to mention other thoughts that will push that task out of commission. It is not a judgment on their abilities; The issue is that we (me included) think we will remember more than we do. Clients sometimes start an appointment with self-flagellation because they forgot to do the task they meant to accomplish between sessions. I empathetically explain that, as far as I can tell, there is nothing wrong with their memory. It is simply a case of having more to remember than our memories can handle. We then explore options to capture the task and set them up to successfully remember to do the task at the right time. Working Memory Our working memories temporarily hold information to work it. We only have four slots available at any given time. (I have more recently read of six slots. Either way, our working memories do not have an infinite capacity to hold onto competing bits of information simultaneously.) According to Dr. Russel Barkley and other experts, that number also decreases as we age. These limited slots translate to a limited capacity to remember various bits of information throughout the day. New information will squeeze out older information. As we walk to another room to retrieve something, any number of possessions in view can trigger competing thoughts so that by the time we reach the room, we have forgotten what we meant to retrieve. External Memories How can we avoid this aggravating trap? We need to transfer the task to an analog or digital external memory. Grabbing the nearest piece of paper to quickly jot down a thought is a typical example of an analog solution. We can all do our future selves huge favors by writing thoughts in a consistent place, like one brightly colored planner. This planner bypasses the all-too-common problem of losing tasks written on tiny slips of paper. Digital external memories can be rudimentary or quite robust. You can quickly ask Siri or Alexa to remind you to do something at a particular time. Alternatively, you can take a few extra seconds to open a robust task app to prioritize and schedule it against competing tasks or delegate it to family members and colleagues who use the same app. The Quicker, The Better Sometimes, the task disappears before we can open our planners and apps. Normal aging, increased stress, depression, and ADHD are a few reasons why this may occur. Whatever the cause, you can try an unusual tactic to keep that task in mind until you can record it: repeat it out loud until you have opened your planner or app to the correct section. This strategy sounds silly, but it works, especially if your phone, laptop, or planner has temporarily gone missing. Another tactic is to use a temporary stop-gap. For example, irrelevant but important tasks or ideas pop up while I work at my desk. Taking the time to transfer the ideas to a planner or app can sometimes lead to more distractions. So, I keep a small, thin dry-erase board within reach to quickly record the thought and return to work. When I need a break, I transfer the ideas and tasks to my app and clean the board. This tactic removes competing thoughts so I can stay focused. The small board size is critical; I can only write down so much information before it is full, and I need to stop, transfer it to my app, and erase it for the next batch of ideas that arise. It’s All About Context When transferring tasks and ideas, document more information than you anticipate needing. Include the current date (including the year), where you left off, the next step, and any other pertinent details. This strategy is a lesson born out of frustration. Years ago, I ran across an important note that could have been helpful, but I had neglected to write the full date and sufficient context. I organize papers and files with most clients. We frequently find cryptic notes. When this happens, they must waste time retracing or repeating steps. For this reason, I recommend transferring more context than they think they will need. One well-written note can save hours on complex projects. Hoping Vs. Committing Transferring tasks out of our heads (and, better yet, scheduling them) serves a secondary yet equally important role. It solidifies the task and represents a commitment to doing it. It can be helpful to tell loved ones, “If you don’t see me capturing it in my planner or app, I have not committed to doing it, as much as I think I have.” This concept especially rings true for those with ADHD who might enthusiastically agree to help with a task but inadvertently forget because they did not capture it outside the working memory. David Allen Says It Best David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, does a fabulous job explaining this habit’s critical nature. When he mentions “RAM" (random access memory in a computer) he is referring to your working memory. On page 23 of my earlier 2001 edition, he writes: “The big problem is that your mind keeps reminding you of things when you can’t do anything about them. It has no sense of past or future. That means that as soon as you tell yourself that you need to do something and store it in your RAM, there’s a part of you that thinks you should be doing that something all the time. Everything you’ve told yourself you ought to do, it thinks you should be doing right now. Frankly, as soon as you have two things to do stored in your RAM, you’ve generated personal failure, because you can’t do them both at the same time. This produces an all-pervasive stress factor whose source can’t be pinpointed.” The best action is to get the task out of our heads, onto paper, or into apps. Your future self will love you for it! Previously, I wrote about using a “parking lot” to remove competing thoughts that otherwise detract from critical daily goals.

What happens when we forget to use a digital or analog parking lot? Every competing thought has the potential to take us off track for minutes or hours at a time. Take last week, for example. Earning the ICD’s ADHD Specialist Certificate was one of my 2023 goals. I was rereading ADHD course notes and happily plugging right along until I read a sentence that was particularly “sticky.” If I do my “future self” a favor by using my dry-erase pad as a parking lot, I stay on track more easily. Then “Future Judith” at the end of the day will feel satisfied with "Past Judith’s" progress. I have been using this "past" vs. "future" self tactic for many years to help initiate tasks that are about as enjoyable as watching paint dry. Typically, my pad is within arm’s reach to park competing thoughts. Sometimes those competing thoughts revolve around other tasks I need to do. Quite often, though, the competing idea starts with an innocuous “I wonder. . . “ I forgot to ensure my pad was nearby on this particular day. Then I read the “sticky” suggestion regarding RSS feeds. I bet you can guess what happened next. “Oh yeah, I tried to set up RSS feeds a few years ago to stay on top of relevant organizing news.” “I wonder what happened with that?” “Oh yeah: I tried setting it up, but it wasn’t working, so I cut my losses and moved on.” “I still think they could help me keep up with the news. I wonder if I just had the wrong idea as to what RSS entails.“ Before I knew it, I had scratched the curiosity itch and felt immediate satisfaction in finally understanding RSS feeds. That is until I looked at the time. A half hour had passed, and I was no closer to finishing the critical task, and it was getting late. The satisfaction immediately morphed into guilt; had "Past Judith" remembered to use my parking lot, I would have quickly parked that curiosity where it belonged, off to the side, so I could continue focusing on my goal. Luckily it was only a half hour, but a half hour here or an hour there is how a day starts with lighthearted hope and ends with a resounding thud. The parking lot is no panacea for all distraction woes, but it gives us a fighting chance to feel satisfied with our efforts by the end of the day. So how about it? There is nothing to lose; how about giving the parking lot a shot? If you want a refresher on how it works, click here. The more you use it, the more you will remember to use it. The more focused you can be on those tasks, the more likely you will feel good about working towards those important goals by the end of the day.  What does a parking lot have to do with organizing? Seemingly nothing, but, plenty. A world of pings and rings distracts us from our intended tasks. Let us not forget that incessant internal clatter, either. It is a miracle that we get anything done with all the noise. For those with ADHD, it is even more challenging to ignore those pings, rings, and internal noise than for a neurotypical individual. According to what I have read online and in various books, we only have four “working memory” slots. Working memory is the section of our brain where we temporarily store information while we work with other information. For instance, to mentally add two large numbers, we must remember the first number, the second number, and also do the addition. I am grossly oversimplifying the concept, but the gist is that we do not have infinite working memory slots to hold multiple thoughts simultaneously. If we happen to pick up a ringing phone as we add those two numbers, the visual process and resulting thought could boot out one of the two numbers. Now you only remember the last number and the new thought. Goodbye, first number; back to the drawing board. Those with ADHD face a more considerable challenge with working memory. The same goes for aging neurotypicals. So, what are we to do if we have important tasks to complete, yet we repeatedly pull ourselves off-task, regardless of our best intentions? We can turn on our phones’ Do Not Disturb or Airplane Mode. We can mute audible or visual cues that alert us of unread emails. What about all those competing thoughts that pop up during every waking hour? I have read varying statistics stating we have anywhere from 6,200 to 10,000 thoughts on any given day. That is a lot of distraction deterring us from essential tasks! So how can we give ourselves a fighting chance of staying focused? We can use a “parking lot.” Years ago, I was in a multi-departmental meeting. There were complex issues to discuss, so naturally, many offshoots grew from the main discussion. I learned a great tactic in that meeting. The facilitator set up a large Post-It easel pad and labeled it “parking lot.” Anytime someone had a related question, concern, or idea that was not on the agenda, we wrote it on the “parking lot” so we did not forget it but could avoid going off-track. Someone later added the parking lot ideas to the next meeting’s agenda or captured it elsewhere to be addressed at a later date. At the time, I found it to be a novel concept. It can truly be helpful and you do not have to spend money to use this tool. Your parking lot could come in various forms:

You might notice that I did not include loose scraps of paper. Sometimes we do not have a choice, but I prefer getting ideas onto or into something that is not easily lost. When working at my computer, I enjoy using a dry-erase board. The board sits within arm’s reach so I can quickly capture the thought instead of impulsively going off-task. As a competing idea pops into consciousness, such as returning a text message, I write, “return Sarah’s text,” on my board instead of halting progress to text her right then and there. It can be a boon for getting things done when combined with a timer and Pomodoro sessions. For the Pomodoro, I set my timer for twenty-five or fifty minutes. When the timer rings, I take a short break. I can stretch, move around, and spend a few minutes attending to those other tasks or scheduling them into my calendar or digital task list. After my break, I can sit down for another focused Pomodoro session. I enjoy my dry-erase board because it has limited space to write. I force myself to calendar or input the task into my app then because I need a fresh slate to write down new ideas that inevitably pop up as I start my next Pomodoro. Additionally, I can avoid dealing with a daunting list of tasks to address at the end of the day when I am already tired. The biggest drawback to this tool is that it is too bulky to use on the go. So, one could employ a daily planner, so long as it contains blank space to write the ideas before they leave the working memory slot. We can use paper pads too. The benefit is that we can quickly capture the thought before it is forgotten. Its Achilles’ heel is that ripped-off papers might add more bulk to an existing pile of clutter. A digital planner or task app can work too. The benefit is that many of us typically have cell phones within arm’s reach, but for me personally, it has a significant drawback. As I age, I notice that fleeting thoughts flee my consciousness much faster than they used to, so I have to get the idea out of my head quickly. A lot could distract me on the way to getting the task into the app, thus knocking the thought out of my working memory until it randomly pops up again later on, usually at the wrong time to address it. To enter the task before the idea evaporates into thin air, I have to:

At any given time during these steps, another thought could race in and knock out the idea I wanted to remember. I am left holding my phone, ready to type, and frustratingly racking my brain for the thought that disappeared into the ether. So, rather than forcing myself to jump through those hoops, I skip the steps by more quickly grabbing my pen and dry-erase board. When I take a break, I schedule any tasks or add them to my digital task app. You can use digital voice assistants too. For instance, if you are working and remember that you need to buy milk tonight, you could launch Google Assistant on your digital device by saying, “OK, Google,” and then, “Remind me to get milk tonight at 7 pm.” The reminder will ring at the appropriate time instead of ruining your focus when you cannot go to the store. Whichever tool you use, a “parking lot” for dumping distracting thoughts can help keep us on track. We can then avoid the dreaded, “It’s 4 pm already! How did that happen? I was supposed to be done, but I just sat down and got started!” Getting those competing thoughts out of your working memory and into a receptacle outside of your memory gives you a fighting chance to get things done that truly matter. Why do so many of us feel like we are spinning our wheels but not reaching our goals? It all boils down to keeping our eye on the prize or “the ONE Thing,” as Gary Keller and Jay Papasan refer to it in their book, The ONE Thing The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary Results. Easy in theory, challenging in practice.

As we focus on a task, distractions seem never-ending. We can start on the right path if we write them down to return to the task at hand. Some might even have well-organized tasks and project lists, or maybe even software devoted to staying organized. Yet after weeks, months, or even years of dedication to our tasks, we can become exasperated when our goals seem as far away as ever. Some may have stopped creating goals altogether because the recurring disappointment is just too painful. Keller says that most of us are doing as much as humanly possible to reach our goals, but the problem is that we should be doing the opposite: we should be “going small.” Instead of completing all those tasks, we must decipher the most crucial task that gives us the biggest bang for our buck. How often do we stop to identify those needle-moving tasks? When running his real estate company, he found that his high performers were not completing their self-assigned tasks during the week. He created a “Focusing Question” to ask every day, and it made a massive shift in his company, Keller Williams Realty. Perhaps you have heard this question in articles or seminars: “What is the ONE Thing I can do, such that by doing it, everything else would be easier or unnecessary?” Before even asking this all-important question, though, we must address six fallacies that lead us down the wrong path. "Six Fallacies" “Everything matters equally” Checking items off task lists feels good in the moment, but where does it lead us? Unfortunately, not far if those tasks were not the best way to move closer to our goals. With great insight, he states, “If your to-do list contains everything, then it’s probably taking you everywhere but where you really want to go.” Instead of trying to do it all, we need to push the famous Pareto Rule (“80% of outcomes result from 20% of preceding factors,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_principle) to the outer limits. Once we have determined what 20% of all tasks will result in 80% of the results, we need to narrow it down to the most significant needle-moving activity. “Multitasking” Thankfully, those of us who ever resented that age-old interview question about multitasking (because it was not our forte) have been vindicated. Multiple studies have now shown that multitasking does not work when competing tasks demand a lot of thinking. Keller dives into more detail: we can switch tasks rapidly and do two things simultaneously, but we cannot focus on two things at the same time. Apparently, multitasking wastes 28% of workdays. Additionally, I have read that it takes our brains up to twenty minutes to return to focus after dealing with a distraction. Thus, multitasking truly seems to be a losing proposition. “A disciplined life” For anyone who feels guilty about a lack of discipline, fear not. Keller argues that what we enviously witness in others is not a rare quality buried deep in the DNA of high achievers. Instead, what we are seeing is a heavy reliance on habit. High achievers only need enough discipline to repeat the necessary task until it becomes a habit. Their daily routines help them reach their goals. They do not have to white-knuckle it through each day with a massive amount of discipline. What a relief to those of us who never felt like we had giant stores of discipline ready to be used at any moment. Completing large decluttering projects becomes much easier when we engage in habit formation. Clients and I spend time removing roadblocks and collaborating on realistic strategies. Those strategies sustain habits that not only help reach organizing goals but also keep clutter at bay. (For more information on habit formation, see my articles on The Power of Habit and Atomic Habits.) Numerous pop psychology articles reference a twenty-one-day time frame to create habits. This number always felt unrealistically low to me, unless we are talking about easily formed bad habits like eating too much junk food or spending too much time on social media. Indeed, Keller references a 2009 study determining that it takes, on average, sixty-six days to create a new habit (some took as little as eighteen days and others two-hundred fifty-four days). Last year I learned that it could take longer for those with ADHD. All this news might feel disheartening if you thought it only took twenty-one days, but I consider it to be good news. While it might take longer than initially expected to create a habit, it now means we have a more realistic timeframe. Hopefully, we will be less likely to quit a new habit on day twenty-five because we erroneously thought it should be old-hat by then. “Willpower is always on will-call” Similar to discipline, we cannot always rely on willpower. Keller references studies that demonstrate diminishing returns. The more we use willpower, the less available it becomes. So, it becomes imperative to tackle our most important tasks first, rather than burn through our reserves on more menial tasks. “A balanced life” For many years, pop culture touted life “balance.” In Keller’s opinion, one cannot reach outstanding achievements without getting out of balance. We have to invest a lot of time and energy into reaching big goals. It naturally means that other tasks will be left undone. We have to learn to be comfortable with the “chaos” of unfinished business. Luckily this does not mean that we abandon everything else forever. What good is a life goal if we sacrifice friends, relationships, and health to achieve them? Probably not much, he insightfully argues. Instead, he instructs us to use “counterbalancing”: we cannot get so far out of balance for so long that we lose everything. He argues that it is ok to be far out of balance in work-life to reach lofty goals. In personal life, it is better to avoid those extremes. “Big is bad” Many of us fear success because it might mean sacrificing too much: dealing with massive levels of stress, losing social connections, or abandoning health. The good news is that as we work towards that big goal, we adapt. We learn how to manage the stressors better as we grow. "The Focusing Question" After addressing fallacies, he dives deeper into the Focusing Question: “What is the ONE Thing I can do, such that by doing it, everything else would be easier or unnecessary?” We might be tempted to drop “such that by doing it” because it feels redundant, but he argues that it is crucial: “This qualifier seeks to declutter your life by asking you to put on blinders. This elevates the answer’s potential to change your life by doing the leveraged thing and avoiding distractions.” Quite frequently, I advise clients to adorn make-believe “horse blinders.” When decluttering, it is easy to get distracted with related but non-essential tasks. By putting on “horse blinders,” we can more easily focus on the most rewarding decluttering action. The Focusing Question is adaptable to both large and small goals. We can insert “right now,” “this year,” or other verbiage after the phrase “that I can do” to fit the need. We can also add qualifiers to address different areas of our lives. For example, “What’s the ONE Thing I can do today for [whatever you want] such that by doing it everything else will be easier or unnecessary?” Ask this question every morning to stay on track. The answers to the Focusing question are crucial. Solutions can necessitate “doable” action, “stretch” action, or activity in the realm of “possibility.” Avoid “doable” steps to reach those all-important life goals because they use our existing tools. “Stretch” activities will take us farther. We might need to research what others are doing so that we can do the same. The task might “stretch” us to the edge of our current skillsets. Reaching lofty life goals necessitates “possibility” actions that are well outside of our current limitations. Similar to “stretch” activities, the first task is to ask, “Has anyone else studied or accomplished this or something like it?” Unlike “stretch” tasks, the answer to that question now becomes our bare minimum effort. We need to go in the same direction as the best performers and then go beyond or potentially plot an entirely novel course. Whether the goal is personal (e.g., decluttering your home) or professional (e.g., becoming an expert in your field), “possibility” tasks are the ones that will get us there. Taking “possibility” action net more significant rewards in the distant future, but how do we avoid the temptation of less critical tasks that net immediate (albeit smaller) rewards? Use his “goal setting to the Now” technique to connect emotionally to distant future rewards, rather than to the smaller immediate reward. We connect someday goals to immediate goals through a series of questions.

He argues that we cannot skip any of these steps because each phrase keeps us emotionally connected to that bigger goal, rather than menial feel-good tasks that take us off course. Avoiding this necessary technique is “why most people never get close to their goals. They haven’t connected today to all the tomorrows it will take to get there. “ "Time Blocking" So now that we know precisely what that ONE Thing is, how do we commit to it amidst competing distractions? We use time blocking. We block off sufficient time on our calendars to devote to the ONE Thing. Everything else needs to happen around this time block. To make blocks work, we need to “get in the mindset that they can’t be moved.” First, we block out free time since we cannot sustain arduous effort without rest. Then we block off four hours to devote to the ONE Thing. He used the popular 10,000-hour theory to create his calculation of four daily hours. (For those who have not started decluttering because it is far too intimidating, try starting much smaller. Even fifteen or five minutes of decluttering a day is better than no minutes, and the fear of starting with just fifteen minutes is much smaller than four hours!) There are a series of moves we can make to protect our time blocks:

We need to have the mindset of mastery to stick to time blocks. This essentially means “becoming your best,” which is a life-long process. When the ONE Thing becomes this important, we are more likely to commit. Additionally, we cannot stop when we reach the current limits of ability. We should use the Focusing Question to determine what we need to learn or what we need to do differently to achieve big goals. "Four Thieves" Last but not least, we need to beware of the four “thieves” that can take us off track:

"A Life without Regrets" In summation, he argues that the best way to live a "life without regrets" is to strive towards those lofty goals. To do that, we must always focus energy and time on that One Thing that will help us get there. So how about it? How many tasks are on your to-do list today: are there too many to realistically complete? Are you setting yourself up to feel like a ping-pong ball in a match between Olympic athletes? Give the Focusing Question a try. You might end your day feeling great instead of exhausted because doing the ONE Thing helped you get that much closer to your most important goals. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed